Savannah Claudia Levin

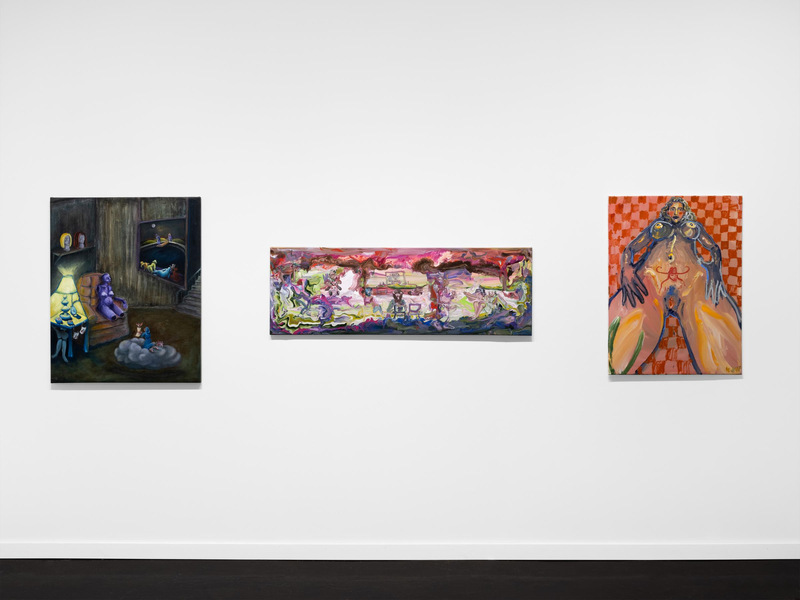

Heartbreak, pathos, kitsch and communion linger in the rich, layered canvases of Savannah Claudia Levin. Born in Togalusa, South Carolina, she grew up in New Orleans, immersed in the vernacular aesthetic of the region. While developing her practice, she worked in her free time at a community printshop, and participated in experimental performance groups she describes as “subversive and fringe.” In one of the poems that accompany her paintings, she writes, “Forget the enormous aloneness that meets us at dawn/and clings dripping home to dusk’s red knees.” Levin’s work hits like a guttural scream encased in resin, and the violence in her paintings is all the more powerful because we encounter it as utterly routine, familiar, expected. The subjects of her study are frequently brutalized, demoralized, bound or otherwise disincorporated, and yet their visages, painted with a resigned malaise, show us that these are not exceptional circumstances, but rather the conditions of their daily life. Levin takes up the subject of redemption, a topic so frequently tied to conservative political ideals or religious zealotry, and breathes new life into it. She almost begs us to pity, pathologize, fetishize or otherwise disregard her wretched figures, and when we feel so inclined, she is waiting with a subtle reminder of our complicity in their strife. Levin refuses to paint on “clean” surfaces, instead foraging for found canvas, stitching pieces together and covering them so fully, at times, that they have the feeling of tanned, oiled leather, or perhaps the wall in an apartment so worn that it must be painted over monthly as unhappy tenants cycle through. She culls from visual traditions as disparate as contemporary religious imagery, German Expressionism, graphic novels, Italian Renaissance, and medical diagrams, building up paint via a highly idiosyncratic process that makes the material facticity, the very record of each successive adjustment, itself at issue; each layer added is worthy of consideration. Language, poetry, and oral history are crucial-the back of her paintings are often as compelling as the front, and the poems she hides there tell us everything we need to know about who she is: a shiftless soul, a compassionate friend, a truth-seeker, a unique voice without parallel or compare. As one of her works quietly proclaims, hers are “thickly calloused palms searching for God.”